Advancing Women Artists (AWA) presents: Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper

Have you ever heard of a Florentine woman painting in the sixteenth century The Last Supper ? That moment in Christ's Passion leading up to Easter, which we commemorate on Maundy Thursday during Holy Week? Neither had I, and that's not surprising, because it was only in 2017 that her work was honoured with a major exhibition at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. This was also the first time ever that this museum had dedicated an entire exhibition to a female artist. Her name: Plautilla Nelli (1524-1588). For centuries, her work hung in the refectory – the dining hall – of the now defunct Convent of Saint Catherine in Cafaggio in Florence, opposite the Convent of San Marco in Piazza San Marco. What is particularly remarkable is that Plautilla Nelli was a nun, a Dominican from this same Convent of Santa Caterina in Cafaggio, where she entered at the age of fourteen in 1538, after the death of her mother, and later became prioress, or head of the convent. She is also the first known female painter of the Italian Renaissance.

During the Renaissance, there was a great tradition of Last Supper paintings. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), for example, painted this theme between 1495 and 1498 in fresco for the refectory of the monastery of Santa Maria della Grazie in Milan (fig. 1). There were many monasteries and abbeys with dining halls where a wall could be decorated in this way. Plautilla Nelli followed in this tradition and defied social conventions by creating an immense work on a theme that until then had been reserved for male artists at the height of their careers, as a kind of testimony to their skills.

Fig. 1. Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, 1495 - 1498, fresco, Milaan, Santa Maria delle Grazie (refrectory)

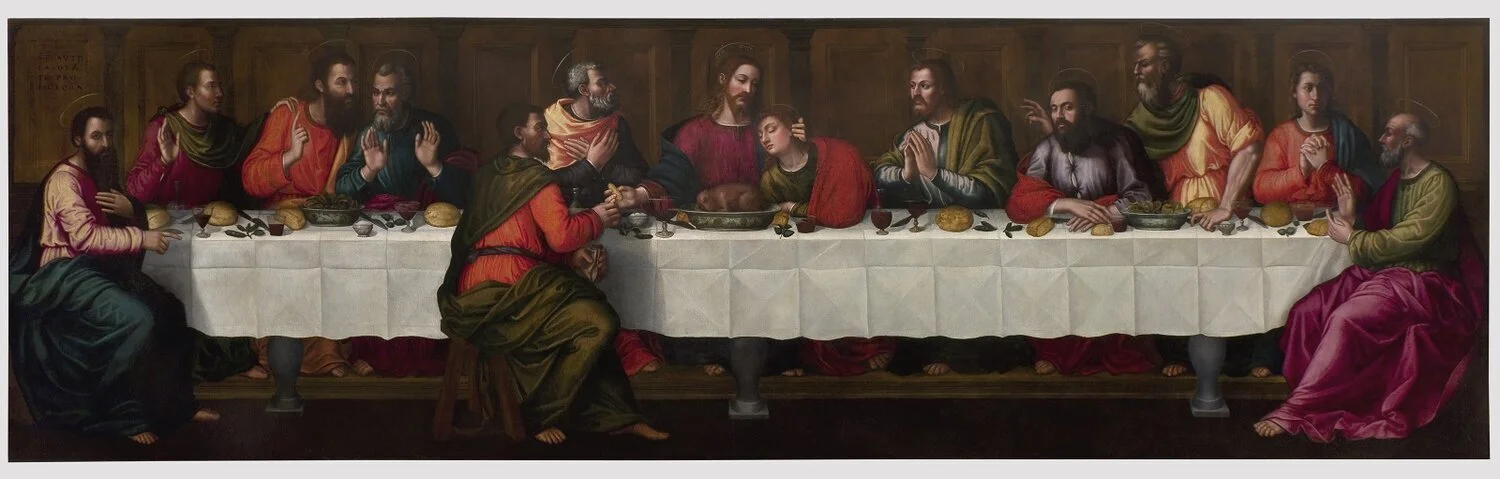

In her version, Nelli, like Leonardo, chooses the moment when Christ predicts that he will be betrayed by one of the disciples present within a few hours and shows the emotions this evokes in them. In doing so, she rivals the way Leonardo Da Vinci depicts the apostles reacting dynamically and emotionally in his The Last Supper. Leonardo's version had become a new concept for the depiction of Last Supper paintings in Florence. Unlike Leonardo da Vinci, Plautilla Nelli places Judas – recognisable by his money bag and the man who will betray Jesus for money a few hours later in the Garden of Gethsemane – on the front side of the table, with his back to the viewer. This was not new and had already appeared in paintings in the fifteenth century.

What is unusual is the decoration of the table: more detailed and elaborate than usual in other versions. In front of Jesus lies a lamb in a dish, referring to the Lamb of God, symbolising the sacrificial Christ. A salad is served in a dish of fine Chinese porcelain, and the folds of the well-ironed and folded tablecloth are clearly visible on the table. It is also unusual that she signs her work in the upper left corner, something that was not done very often at the time (fig. 2). It is as if she wants to be remembered for eternity.

Fig. 2. Last Supper signed by Plautilla Nelli: ‘S. Plautilla orate pro pictora’

(translation: ‘Sister Plautilla, pray for the paintress’)

Plautilla Nelli (fig. 3) was self-taught. She began her artistic career in the convent by making miniatures, an art that – as recent research has shown – was practised not only by monks but also by many nuns. She was well known in her own time, as the artist biographer Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) praises her work in his Vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri (Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Architects, Painters, and Sculptors, from Cimabue to Our Times, ed. 1550 and 1568). Not in a separate Vita, but in the only ‘Woman's life’ he describes in the 1568 edition: that of the Bolognese sculptor Properzia de'Rossi (1490-1530). In it, he honours, alongside Properzina de'Rosssi herself, all kinds of other artistic women from Greek and Roman history and from his own time, including Plautilla Nelli. He writes: “After she [Nelli] had gradually begun sketching and copying in colour the sculptures and paintings of the great masters, she completed a number of works with great diligence that amazed our craftsmen”.

In the convent, Plautilla Nelli set up a large studio, where she was undoubtedly assisted by a number of talented fellow sisters. She inherited drawings by the famous Fra Angelico (1395-1455), who lived and worked in the monastery of San Marco opposite and is said to have been influenced by the works of famous predecessors and contemporaries such as Perugino (1446-1523), Andrea del Sarto (1486-1530) and Giovanni Antonio Sogliano (1492-1544). Nevertheless, in 2006 only three works were attributed to her; today there are about seventeen.

Fig. 3. A presumed self-portrait of Sister Plautilla Nelli, or at least a Dominican nun with a paintbrush, artist unknown.

Her Last Supper hung in the refectory of her convent for centuries. It survived the Napoleonic suppression of religious orders and the unification of Italy with the accompanying expropriation of church property. In 1808, the painting was transferred to the convent of the Chiesa di Santa Maria Novella, where it also hung in the refectory for many years. In the twentieth century, it was rolled up and stored for thirty years, but it survived the flood of 1966, the worst flood ever in Florence caused by the Arno River bursting its banks. Numerous works of art stored in the cellars of museums and monumental buildings were damaged in the process. Florence is still traumatized by this event.

In October 2015, the work was transferred, still rolled up, to the restoration workshop of the Florentine Rosella Lari in the Oltrarno district, on the other side of the Arno. This is still the artistic part of Florence, full of workshops of designers and craftsmen. The work was in very poor condition and the restoration took four years. In the autumn of 2019, it was completed and, after a short ceremony, Plautilla Nelli's Last Supper was placed in the museum of the Chiesa di Santa Maria Novella (fig. 4-10).

Fig. 4. The enormous canvas – measuring 200 x 700 cm and in very poor condition – in the studio of restorer Rosella Lari in Florence.

Fig. 5. Detail: Jesus and Johannes, before restoration …

Fig. 6. … and after restoration ….

Fig. 7. Restorer Rosella Lari at work …

Fig. 8. In autumn 2019, the work arrives, packed, at the Chiesa di Santa Maria Novella ...

Fig. 9. …it takes quite an effort to hang it up

Fig. 10. … in the museum there: Plautilla Nelli's Last Supper in its final location. I still don’t understand why they hang it so high. I would love to see it nearby.

And the story continues...

The discovery of Plautilla Nelli and the restoration of her Last Supper would never have been possible without the extraordinary efforts of American journalist, writer and philanthropist Jane Fortune (1942–2018). In 2006, she stood face to face with another work by Plautilla Nelli, The Lamentation of Christ, in the San Marco Museum in Florence, and she was astonished (fig. 11). Why did she not know this female artist? She decided to provide funds for the restoration of the work. She became further fascinated by Nelli and wondered how many other works by her and other unknown female artists might still exist. ‘Where are they, actually?’ became her guiding question, which soon turned into a personal mission: to make works by female artists from the past visible again. To this end, Jane Fortune founded the Advancing Women Artists Foundation (AWA) in Florence in 2009.

Fig. 11. Plautilla Nelli, The Lamentation of Christ, 1569?, oil on panel, 288 x 192 cm,

Florence, refectory of the San Marco Museum, restored by AWA in 2006

Jane Fortune came from Indiana in the United States and was soon nicknamed ‘Indiana Jane’ in Florence (fig. 12). With a team of experts, she set out to find lost and forgotten treasures that were gathering dust in depots or moldering on the walls of churches, monasteries and other monumental buildings. In 2008, she wrote with co-author Linda Falcone the book Invisible Women about this subject. Jane and her team contacted museum directors, first in Florence and later throughout Tuscany, raised awareness of the issue, conducted research and managed to secure funding through their relentless efforts. As a result, some seventy works of art by female artists from 1400 to 2000 have now been rescued from oblivion, are documented, restored and exhibited, including artworks from Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653), Violante Siries Cerroti (1709-1793), Elisabeth Chaplin (1890-1982), Felicie de Fauveau (1801-1886) and Leonetta Pieraccini Cecchi (1882-1977).

Although Jane Fortune initially wanted to establish a museum for these female artists in Florence, as a tribute to the city she loved so much, she ultimately decided that this was not the way forward. She chose to reveal all her efforts to the world virtually, so that museums and experts worldwide could continue to benefit from AWA's findings.

Fig. 12. Jane Fortune, founder of the Advancing Women Artists Foundation (AWA), 1942–2018

In 2017, Fortune announced that she would be ending her involvement with AWA with the unveiling of the restored The Last Supper by Plautilla Nelli, the painting that had become so dear to her. With the rescue of this masterpiece for posterity, Fortune felt that she had “done her part for Florence”. She wanted to return to the United States to devote her energy to all kinds of other projects, including the establishment of the Jane Fortune Fund for Virtual Advancement of Women Artists, through which she wanted to collect and compile the AWA research into the world's largest international database of female artists, called: A place of their own. The unveiling of The Last Supper was planned for 2019, but Jane died in 2018, aged 76.

Unaware of this background, I subscribed to the AWA newsletter in 2018. I thought it was a wonderful institution and continued to follow their work with interest from the Netherlands. That is how I learned about the unveiling of Nelli's Last Supper in the autumn of 2019: a special moment for the organisation, in fond memory of its founder. And so, in December 2020, I was a bit shocked by the announcement from the then current director of AWA, Linda Falcone, that AWA would be closing down permanently.

After all, as Falcone writes in that newsletter, AWA was never intended to be permanent. AWA was launched in 2006 to raise awareness among Florentine and later Tuscan museums and their staff about the work of female artists. It did so by actively searching for their works, conducting archival research, restoring the works where necessary and thus preserving them for the future, and publicising all this through symposia, newsletters, etc. The intended result was to raise awareness that there was still much to discover in the museum depots, that there was still much work to be done to reveal all the unknown treasures, and that in Florence alone there had been many more female artists than the history books would have us believe. It was high time that this story was told, but that message has now been received. Nowadays there is much more attention on female artists of the past. AWA has done its job and is passing the baton back to the museums and their staff: “AWA's mission is truly accomplished,” says Falcone. As part of the legacy of AWA and Jane Fortune, an image archive of over 2,500 images will remain digitally accessible to researchers worldwide.

We owe Jane Fortune and her staff a debt of gratitude for the great service they has rendered to the art world. The other half of the world's population is slowly catching up in the art world!

Meer info: www.advancingwomenartists.org

NB: This article is translated with the help of Deep.L and afterwards corrected.

NB. Fig. in front: Plautilla Nelli, The Last Supper, 1568, oil on canvas, 200 x 700 cm, Florence, Museum of the Chiesa di Santa Maria Novella

NB. Restorer Elizabeth Wicks has worked extensively on restorations and praises AWA: "In recent years, thanks to AWA, female conservators have had wonderful opportunities to work on art by women, which was hardly the case in the past. As a result, since the great flood in Florence in 1966, art conservation has become primarily a female domain.”

NB. Mélanie Struik (1955), the writer of this article is a Dutch art historian, graduated in 2018 at the University of Amsterdam. In 2020 she started with her website Melaniekijktkunst.nl, writing in Dutch about art with a focus on Early modern Italian art and the position of women as artists and patrons in the past. On that part there is a world to discover. She started to publish an AI-translated English version of her articles on her website, which can be found in the menu under English versions. There are more to come.

Sources:

. AWA website and Wikipedia.

. B. de Klerck, “Speuren naar vergeten schilderessen” (Searching for forgotten female

painters), NRC, 05-02-2019, p. C3.

. https://mariellelassche.nl/plautilla-nelli/.

. Georgio Vasari, Vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino

a' tempi nostri (The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, from

Cimabue to Our Times), ed. 1550 and 1568, .

. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/renaissance-woman-plautilla-nelli-s-last-supper-

unveiled-in-florence

Image credits:

Fig. in front: AWA website

Fig. 1: https://advancingwomenartists.org/news/press-room

Fig. 2: https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Het_Laatste_Avondmaal_(Leonardo_da_Vinci)#/ media/

File:Leonardo_da_Vinci_(1452-1519)_-_The_Last_Supper_(1495-1498).jpg

Fig. 3: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Plautilla_Nelli.jpg

Fig. 4 to 10: http://advancingwomenartists.org/news/press-room

Fig. 11: http://advancingwomenartists.org/artists/plautilla-nelli/lamentation-with-saints

Fig. 12: http://advancingwomenartists.org/news/press-room