AWA and the Forgotten Italian female artists of yesteryear: ‘Una Donna universale’, the multi-talented Arcangela Paladini

I don't remember how it started, but at some point I began receiving occasional news items from the Advanced Women Artists Foundation (AWA) in Florence. AWA was founded in 2009 by American philanthropist Jane Fortune (fig. 1). As a young girl, she spent a gap year in Florence and fell head over heels in love with the city and its artistic treasures. Initially, her interest was focused on the painter Jacopo Pontormo (1494-1557), but years later, in 2006, at a book market in Palazzo Corsini, she came across a work in English about Plautilla Nelli (1524-1588), a sixteenth-century nun and prioress of a convent. She turned out to be the earliest known female artist in Florence. I previously wrote an article about Plautilla Nelli, whom I learned about through the work of Jane Fortune.

Fig. 1. Jane Fortune in 2009

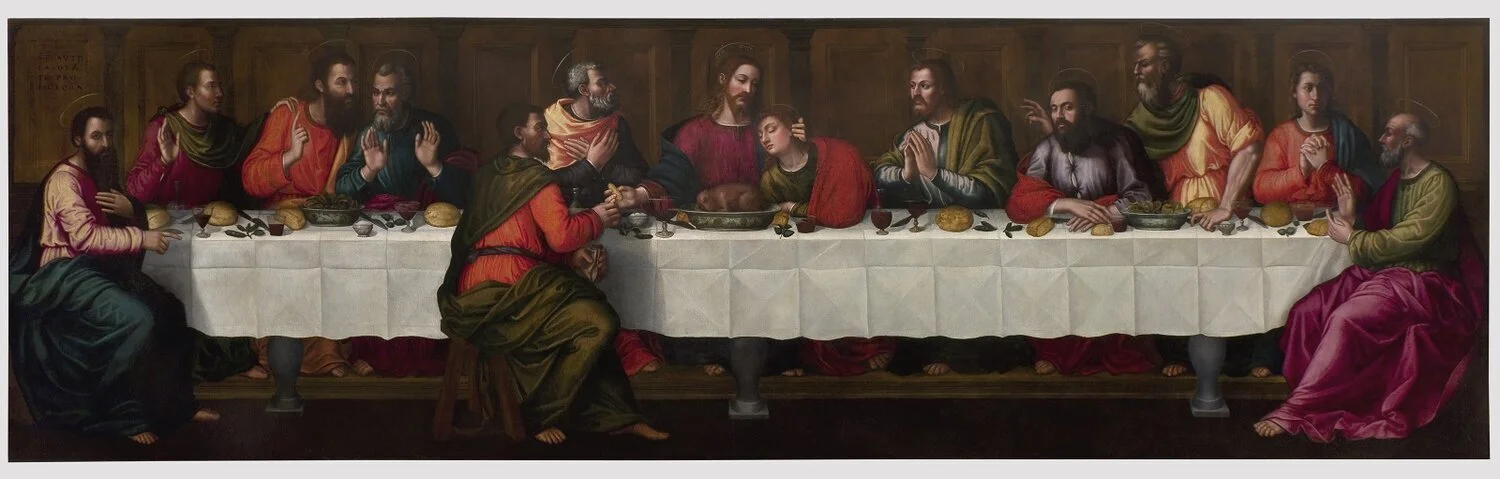

Jane Fortune investigated and found several works by Nelli, all in poor condition. This led her to wonder whether there were other female artists whose work was gathering dust in the cellars of Florence's many churches and the depots of its numerous museums. She made it her personal mission to rescue these women from obscurity and showcase their work. AWA became the vehicle for this, and not without results. Together with art historians and restorers, she put the spotlight on five centuries of female creativity. In her 2009 book Invisible Women, she noted that at that time only 138 paintings by female artists were on public display in Florence and that in all likelihood another 1,500 works were in storage. She raised funds and had forty works restored, including sculptures. And so Plautilla Nelli's immense Last Supper (200 x 700 cm) was also restored. In 2019, it was given a place in the Museo della Chiesa di Santa Maria Novella (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Suor (sister) Plautilla Nelli, Last Supper, 1568

AWA ceased operations in 2021. Its driving force, Jane Fortune, had passed away from cancer in 2018 – sadly, she did not live to see the Last Supper returned to its place – and the conviction grew that Florence could now manage without AWA. The subject had become so ingrained in the minds of museum directors in Florence that AWA's efforts were no longer necessary, was the reasoning.

In AWA's farewell email in July 2021, I found a map and a list of names of art institutions in Florence and names of female artists who could be found there. This overview turned out to come from the book Invisible Women, which Jane Fortune had written in 2009 together with Linda Falcone, her right-hand woman at AWA. The information was somewhat outdated but still valuable (fig. 3, 4, 5). I decided to search for these women artists in Florence. In September 2022, I travelled to Florence, bought the book Invisible Women and started my quest.

Fig. 3. Cover of Invisible Women by Jane Fortune and Linda Falcone

Fig. 4. Overview of places in Florence were you can find works of arts of female artists from the past

Fig. 5. With the corresponding map

A little bit of background on the storage of Florentine collections

A large part of the works in Florence comes from the enormous collection of the highly influential De'Medici family, who rules the city from 1434 to 1743. Among them are a number of great patrons of the arts. The collection has been then expanded – through clever marriages – with works collecte over the centuries by the rulers of the Lorraine dynasty and later the Savoy dynasty. And then, in 1861, Italy becomes a unified state with a central government.

Fig. 6. Terracotta bust of Lorenzo I de Medici, Il Magnifico, from the fifteenth or sixteenth century, probably based on a similar wax sculpture from 1478 by Andrea del Verocchio and Orsini Benintendi

And then there is an interesting development. Under the influence of the Enlightenment, whose thinkers propagate that reason can bring humanity material and spiritual well-being, religious institutions such as churches and monasteries are increasingly viewed with suspicion. The Roman Catholic Church is gradually seen as a counterforce that hinders the development of tolerance, scientific spirit and liberal thinking, and is accused of practising fanaticism. Secularism is rampant, with the result that the state of Italy confiscates many ecclesiastical treasures, buildings and their contents. This separates these works from their original location and they are stored in random places. It becomes one big mess, especially considering that many of these works are unsigned. Later in that century, this strict policy is somewhat relaxed, church buildings are allowed to reopen, and the institutions are given back their work, but not what was previously theirs.

Fig. 7. Museo Stefano Bardini in Florence, an example of a monastery that became a museum

Fig. 8. Interior of the Museo Stefano Bardini in Florence

Napoleon also loots another 63 masterpieces, which are given a place in the Louvre, but fortunately they a return in 1814 (fig. 9). Then, in 1966, Florence is hit by a major disaster: the Arno River overflows and a large part of the city is flooded, with water reaching metres high. When you consider that most museums have their depots in the basement many works of art are lost and, in the chaos of the rescue efforts, many works also loose their original location. This makes it very difficult to trace the works later on. This flood is still a huge trauma for the city. Everywhere you walk in the city centre, you see marks and messages on walls showing how high the water rose at the time (fig. 10, 11, 12).

This is the situation that Jane Fortune and her team encounters when they begin their search in 2008. They have to work their way through this chaos. Hats off to them for all their efforts, focusing on female artists from the Cinquecento onwards: a focus on five centuries of art history.

Fig. 9. George Cruikshank, The Removal of Italian Art Treasures, 1815, caricature from The Life of Napoleon, A Hudibrastic Poem in Fifteen Cantos, 1815

Fig. 10, The Arno River in Florence bursts its banks on 4 November 1966

Fig. 11. Ravage in the Church of Santa Croce

Fig. 12. Volunteers rescue mud-covered art from the cellars of the Palazzo Vecchio in the heart of Florence. © Getty Images

My quest for the forgotten female artists of yesteryear

During my own search, I visite eight locations: the Uffizi Gallery, Casa Buonarroti, Palazzo Pitti, the Accademia Gallery, the Church of Santa Maria Novella, the San Marco Museum, the San Salvi Museum, and the Church of Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi. These were all freely accessible and I was able to enter without needing a letter of recommendation. Experience soon teaches me that I will certainly not find all the works listed in the book Invisible Women. Many of the works are either no longer on display, or the room where they hang is not accessible to the public. Some works are also absent due to restoration or on loan for an exhibition elsewhere. Nevertheless, I encounter a number of interesting female artists both in the museums and churches and in the book. The internet helps me to find out more about them.

In this article, I will start with one of them and introduce the early seventeenth-century Arcangela Paladini. In subsequent articles, I will focus on other interesting female artists of the early modern period.

Arcangela Paladini

Ever heard of Arcangela Paladini (1596-1622)? She must have been stunningly beautiful. According to her contemporaries, she also has a heavenly voice, living up to her first name: Arcangela means archangel. Arcangela is hugely successful in her own time. She is born in Pistoia (Tuscany) as the daughter of the painter and sculptor Filippo di Lorenzo Paladini (1544-1616). She has two older half-brothers from her father's previous marriage, two sisters and a younger brother.

As a young child, she moves to Pisa and enjoys experimenting in her father's studio. She copies his work and, with her small, nimble fingers, I imagine, made designs for embroidery. Her father recognises her talent and encourages her. At a very young age, she develops into an accomplished painter, singer, instrumentalist and poet. An 18th-century source states that she “demonstrated such a high level of skill in each of these areas that she aroused amazement, not only among her fellow citizens but also among visitors who came to Pisa because they wanted to see and hear this young virtuosa”.

This attractes the attention of the Medici court in Florence, first of Christina of Lorraine (1565-1637), wife of Fernando I De’Medici (1549-1609), Grand Duke of Tuscany, and also to the next generation: Grand Duchess Maria Magdalena of Austria (1589-1631), wife of Cosimo II de’Medici (1590-1621), the son of Ferdinando I (fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Justus Sustermans, Grand Duchess Maria Magdalena of Austria with her son, 1620, oil on canvas, Florence, Palazzo Pitti

In 1609, Grand Duchess Maria Magdalena invites Arcangela Paladini to come to Florence. She is just thirteen years old at the time, and her father has died the year before. Maria Magdalena arranges for Arcangela to live in the convent of Saint Agatha, one of the most prosperous convents in the city, where Arcangela remains for four years and where attention is paid to her artistic development. She becomes an apprentice to court painter Jacopo Ligozzi (1547-1627).

The Grand Duchess has a hand in the marriage Arcangela enteres into at the age of seventeen: to the Flemish tapestry weaver Jan Broomans, who also workes for the Medici court. She apprentices with him and quickly mastered the craft: Arcangela and Jan also become partners in work. In 1618, this happiness is crowned with the birth of a daughter named Maria Magdalena, a tribute to Arcangela's benefactor.

Grand Duchess Maria Magdalena is a patron of the arts of the highest order. She arranges commissions for Arcangela and introduces her to her husband, Cosimo II, who in turn introduces Arcangela to his network. In 1621. Maria Magdalena commissions her to paint a self-portrait and ensures that all members of the court see it. It becomes a beautiful test of skill that is given a place of honour in the Grand Duchess's private quarters.

Arcangela receives many more commissions, all of which were documented, but unfortunately these works seem to have disappeared or are languishing in back rooms and depots. Or they have been wrongly attributed to other artists and not recognized as her work. Her self-portrait is the only work of hers that has survived (fig. 14) and was later given a place in the famous Corridoio Vasariano in Florence.

Fig. 14. Arcangela Paladini, Self-portrait, 1621, oil on canvas, 54 x 43 cm, Florence, Uffizi Gallery. A beautiful portrait with an almost modern feel to it – you would never guess that it was painted in 1621, would you?

The Corridoio Vasariano

There are some interesting facts to share about the Corridoio Vasariano. It serves as an escape route for the De'Medici family and members of the elite from the Palazzo Vecchio, the city's administrative centre, to the Palazzo Pitti on the other side of the Arno, the private residence of the De'Medici family. Life is dangerous in the sixteenth century. Cosimo II's father Cosimo I (1519-1574) commissiones Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), whom we also know as a painter and artist biographer, to build it in 1565. This corridor, which soon becomes associated with Vasari's name, is a one-kilometre-long elevated walkway that runs through the Uffizi, where the officials lived, and crosses the Arno at the Ponte Vecchio. Cardinal Leopoldo De'Medici (1617-1675) later exhibites his collection of sixteenth and seventeenth-century artworks there. The gallery is still famous, partly because of the many self-portraits of famous artists from its own time and later periods that hang there. Initially, the De'Medici commissiones artists to paint these portraits, but they soon began receiving self-portraits as gifts because it is considered a great honour for artists to have their work displayed there (fig. 15, 16) .

Fig. 15. The Vasari Corridor, which runs from the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence across the Ponte Vecchio over the Arno towards the Palazzo Pitti

Fig. 16. Interior of the Vasari Corridor in Florence

Back to Arcangela Palladini. We may have a second image of her after all. She most likely knew the Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656), who is also at the Medici court in Florence at the same time. Arcangela may have modelled for one of Artemisia Gentileschi's works - Saint Cecilia (fig. 17). From the fifteenth century onwards, Saint Cecilia is often depicted as the patron saint of music. It will not be illogical for her to ask Arcangela to model for this saint because of her heavenly singing voice. There seems to be a resemblance to Arcangela's self-portrait (see the opening image of this article).

Fig. 17. Artemisia Gentileschi (attributed), Saint Cecilia playing a harpsichord (resembles a piano, sounds like a lute), 1620, oil on canvas?, 92 x 72 cm, Italy, Trento (private collection). Is Arcangela Paladini the model here?

Arcangela's musical talents are widely appreciated at the Medici court. She performes there regularly, sometimes together with the renowned composer, harpsichordist and soprano Francesca Caccini (1587 - c. 1641). Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger (1568–1636) – writer, poet and great-nephew of the famous artist – also chooses her to sing in his comedy La Fiera, which was performed at court in 1618. In a play performed in Florence in 1619, she playes the role of Saint Cecilia, undoubtedly also a reference to her singing skills. She has been described with admiration as ‘Madama Serenissima’ or ‘La Cantrice della Serenissima’, an honorary title for royal persons. A bright future seemes to lie ahead.

But it was not ment to be. Arcangela dies in 1622, and we do not know what happend. What we do know is that this has not gone unnoticed. The Grand Duchess is greatly saddened. She commissiones sculptor Antonio Novelli (1600-1662) to create a marble tomb with a sculpted bust of Arcangela herself – yet another image of her - flankes by reliefs of Apelles - considered the greatest painter of antiquity and holding a palette - and the goddess Athena with a harp, as patroness of - among other things - the (vocal) arts. Beneath the bust is an inscription of the contemporary poet Andrea Salvadori (1588-1634): 'She sang for Etruscan kings and now sings for God. She was equal to Pallas Athena in needlework, to Apelles in painting and to the Muses in song ... Sprinkle this stone with roses for her, innocent in her heavenly song lies here the Siren of Tuscany and the Muse of Italy' (fig. 18).

Fig. 18. Tomb of Arcangela Paladini in the Church of Santa Felicita in Florence

As a sign of her extraordinary appreciation for Arcangela Paladini, Mary Magdalene has the tomb placed in the vestibule of the De'Medici family church, Santa Felicitá, right next to the Vasari Corridor. A greater honour is unimaginable, and this tomb can still be found there today. The Grand Duchess also arranges a dowry for Arcangela's daughter Maria Magdalena in case she enteres the convent, which she does when her father remarry in 1623. She receives this dowry on one condition: that if she takes a new name – when entering a convent, you chose the name of a saint – she will choose ‘Arcangiola’. In this way, her mother's name will continue to be heard in the world, according to the Grand Duchess.

Despite the very favourable circumstances under which Arcangela Paladini has been able to work, her work has been forgotten over time. Only her remarkable self-portrait remains. And even this work can only be seen by a very select group of people who have access to the Vasari Corridor that has been closed to the public for a very long time. It is open now, but only for guided tours and I’m still not sure that the portait can be seen there. You have to ask the tourguide.

It is very likely that there is still work by Arcangela Paladini in the depots. There is still so much work to be done to bring her work and that of other female artists of yesteryear to light. Let's hope that with the current increase in interest in the forgotten women of art history, more will become clear about them. The work of Jane Fortune and the other staff at AWA will certainly contribute to this.

—————————————————————

NB. This article is translated with the help of Deep.L and afterwards corrected.

NB. Mélanie Struik (1955), the writer of this article is a Dutch art historian, graduated in 2018 at the University of Amsterdam. In 2020 she started with her website Melaniekijktkunst.nl, writing in Dutch about art with a focus on Early modern Italian art and the position of women as artists and patrons in the past. On that part there is a world to discover. She started to publish an AI-translated English version of her articles on her website, which can be found in the menu under English versions. There are more to come.

Image credits:

Cover and fig. 14. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/63/Arcangela_Paladini_-_Self-portrait_in_Uffizi_Gallery.jpg

Fig. 1. https://www.groene.nl/artikel/jane-fortune-9-augustus-1942-23-september-2018 Fig. 2.http://advancingwomenartists.org/news/press-room Fig. 6. https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorenzo_I_de%27_Medici#/media/Bestand:Verrocchio_Lorenzo_de_Medici.jpg

Fig. 9. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Cruikshank,_Seizing_the_Italian_Relics,_1815.jpg

Fig. 10, 11.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/04/florence-flood-50-years-on-the-world-felt-this-city-had-to-be-saved

Fig. 12. https://www.historytoday.com/history-matters/florence%E2%80%99s-mud-angels

Fig. 13. https://nl.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bestand:Maria_Magdalena_van_Oostenrijk.jpg

Fig. 14. https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/self-portrait-arcangela-paladini

Fig. 15.https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/57/CorridorVasari.jpg

Fig. 16.https://www.visitflorence.com/blog/vasari-corridor-reopen-2021/

Fig. 17.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St-cecilia.jpg

Fig. 18.https://www.artinsociety.com/forgotten-women-artists-1-arcangela-paladini.html

The remaining photos were taken by the author.